Same-Origin Policy and CORS

There are three key concepts to understand CORS:

- Origins and the Same-Origin Policy (SOP)

- Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS)

- Sending Requests Between Origins

Modern web applications often use resources and data from multiple domains or web sites. Web applications load images, fonts, and even JavaScript from external domains. When an HTML page or other resource on one domain instructs a browser to load content from another domain, the resulting request is a cross-origin request.

Browsers implement the Same-Origin Policy (SOP),1 a protective mechanism that limits how JavaScript code can interact with such requests and their responses. Developers can use Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS)2 to selectively relax the SOP on their applications.

JSON with Padding (JSONP)3 is another technique for bypassing the SOP, but it has multiple security concerns and has largely been replaced by CORS.

We will explore these mechanisms and their security implications. We will also cover how to send cross-origin requests in JavaScript.

Origins and the Same-Origin Policy (SOP)

The first concept needed to understand CORS is Same-Origin Policy, two considerations are:

- Understand what an origin is in the context of web applications

- Understand the Same-Origin Policy

In the context of web applications, an origin is a subset of a URL. It is the combination of a protocol,1 a hostname, 2 and a port number.3

Let’s review a sample URL and determine its origin.

1

2

URL: https://www.example.com/blog/

Origin: https://www.example.com

Our sample URL’s protocol is HTTPS. Its domain is www.example.com. The URL does not include an explicit port number, so its origin uses the default port number of HTTPS (443). Notice that the origin includes the entire domain name, including the “www” subdomain, but does not include the path value (/blog).

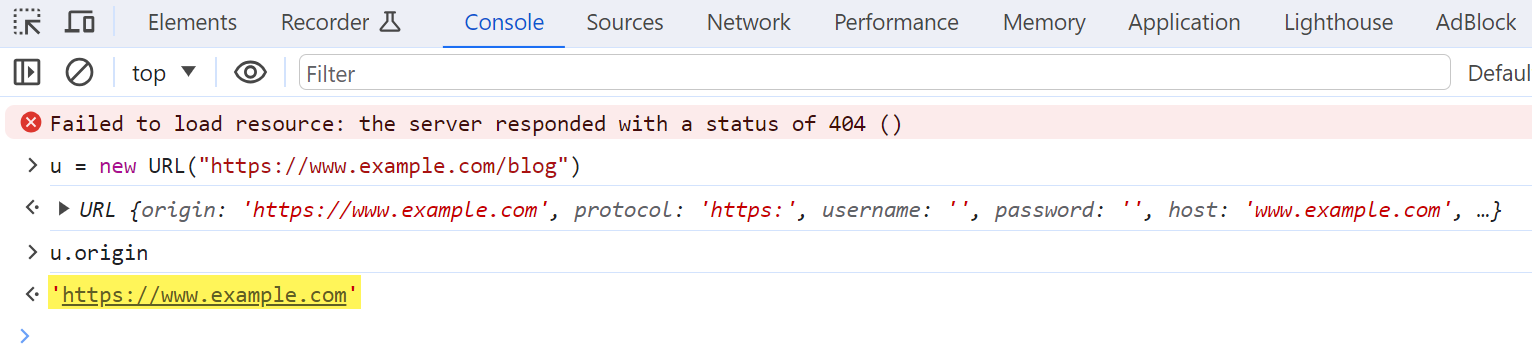

We can also use JavaScript to derive the origin of a URL. The URL4 object includes an origin5 property that returns the URL’s origin.

Let’s try it out. We’ll need to open our web browser and then open its JavaScript Console with [F12]. We can then declare a new URL object by typing u = new URL(“https://www.example.com/blog”) and pressing [Enter]. We can then check the URL’s origin by typing u.origin and pressing [Enter].

The origin property returned https://www.example.com.

We can also read the origin6 property on the global scope after loading a web page. In our browser’s JavaScript console, calling self.origin is essentially the same as calling window.origin. Both properties will return the origin of the currently loaded web page.

Now that we understand origins, let’s review the Same-origin Policy (SOP).

Same-Origin Policy (SOP)

The SOP is a protective mechanism that web browsers implement that prevents resources loaded on one origin from accessing resources loaded from a different origin. A resource can be an image, HTML, data, JSON, etc.

Without the SOP, the web would be a much more dangerous place, allowing any website we visit to read our emails, check our bank balances, and view other information from our logged-in sessions.

Instead, SOP allows cross-origin requests, but blocks JavaScript from accessing the results of the request. This might seem confusing since plenty of websites have images, scripts, and other resources loaded from third-party origins.

Let’s consider an example in which https://foo.com/latest uses JavaScript to access multiple resources. Some resources might be on the same domain, but on a different page. Others might be on a completely different domain. Not all these resources will successfully load.

| URL | RESULT | REASON |

|---|---|---|

| https://foo.com/myInfo | Allowed | Same Origin |

| http://foo.com/users.json | Blocked | Different Scheme and Port |

| https://api.foo.com/info | Blocked | Different Domain |

| https://foo.com:8443/files | Blocked | Different Port |

| https://bar.com/analytics.js | Blocked | Different Domain |

In the examples listed in the table all of the requests would be sent, but the JavaScript on https://foo.com/latest would not be able to read the response of those marked as “Blocked”.

How do web pages embed images or other content from different domains? SOP enforcement depends on the type of cross-origin request, which can be divided into embeds, writes, and reads.

With the continued use of content delivery networks (CDN),1 embeds might be the most common type of cross-origin interaction. Many web applications embed JavaScript files, images, fonts, and videos from CDNs or other external domains. It is important to note that embedding JavaScript in this way effectively bypasses the SOP. In other words, the embedded JavaScript code would be able to read the contents of the embedding page.

In other words, if we were to visit the example https://bar.com/analytics.js directly, it could not access the contents of https://foo.com/latest. However, if https://foo.com/latest loads the contents of https://bar.com/analytics.js with a <script></script> tag, the JavaScript code would have access to the page contents.

Cross-origin writes are links, redirects, and form submissions. We can think of writes as one-way traffic. One origin can initiate a write to a different origin, but it cannot access the response. For example, https://foo.com/latest can have a form that sends a POST request to https://bar.com, but SOP will block JavaScript on https://foo.com/latest from accessing the response. Accessing the response would constitute a read interaction, which are all typically blocked by SOP.

While this page focuses on SOP and CORS, it is worth mentioning cross-site request forgery (CSRF)2 attacks, which exploit SOP allowing cross-origin writes. Attackers use CSRF attacks to perform actions as the victim user. For example, an attacker might embed a hidden form in a page that automatically submits to perform some action, such as changing a password, creating a new user, or otherwise manipulating the user’s account and application access.

CSRF vulnerabilities have become less common in recent years since many frameworks include CSRF protections. Web applications can also set the SameSite3 attribute on cookies to indicate how browsers should handle the cookies on cross-origin requests. If a cookie has the SameSite attribute set to Lax, browsers will not send the cookie on cross-origin requests.

CSRF attacks usually require victims to have an active, authenticated session on the target site. If the browser doesn’t send session cookies on the CSRF request, the attack will typically fail. Most browsers will default cookies to SameSite=Lax if no other SameSite value is set.4

Web applications can use Cross-origin Resource Sharing to enable cross-domain reads.

Cross-origin Resource Sharing (CORS)

Now that we understand what Same Origin Policy is we can deep dive into CORS and:

- Understand the basics of Cross-origin Resource Sharing

- Understand what headers are available on CORS requests

- Understand how web servers enable CORS

- Understand the basic security concerns of enabling CORS

Exploring CORS

We need to create an entry in our /etc/hosts file so that we can access the SOP and CORS Sandbox VM at http://sop-cors-sandbox.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

kali@kali:~$ sudo mousepad /etc/hosts

kali@kali:~$ cat /etc/hosts

127.0.0.1 localhost

127.0.1.1 kali

# The following lines are desirable for IPv6 capable hosts

::1 localhost ip6-localhost ip6-loopback

ff02::1 ip6-allnodes

ff02::2 ip6-allrouters

192.168.50.155 sop-cors-sandbox

For now, we only need to start the SOP and CORS Sandbox machine listed below and update /etc/hosts with the corresponding IP address on our Kali machine before starting our work.

In its simplest terms, CORS instructs a browser to allow certain origins to access resources from the server. It allows web applications to intentionally loosen SOP restrictions on themselves by specifying which external domains can access resources and how those domains can access the resources. Web applications can enable CORS by setting certain headers on server responses.

Remember, the SOP blocks JavaScript and our browsers from accessing cross-origin resources, but it does not block the outgoing requests for such resources. With CORS enabled on the remote server, JavaScript running on the application initiating the request can then access the response.

For example, to allow https://foo.com to load data from https://api.foo.com, the API endpoint must have a CORS header allowing the https://foo.com origin. If the API endpoint does not enable CORS, then our browser will enforce the SOP and block JavaScript from accessing the response.

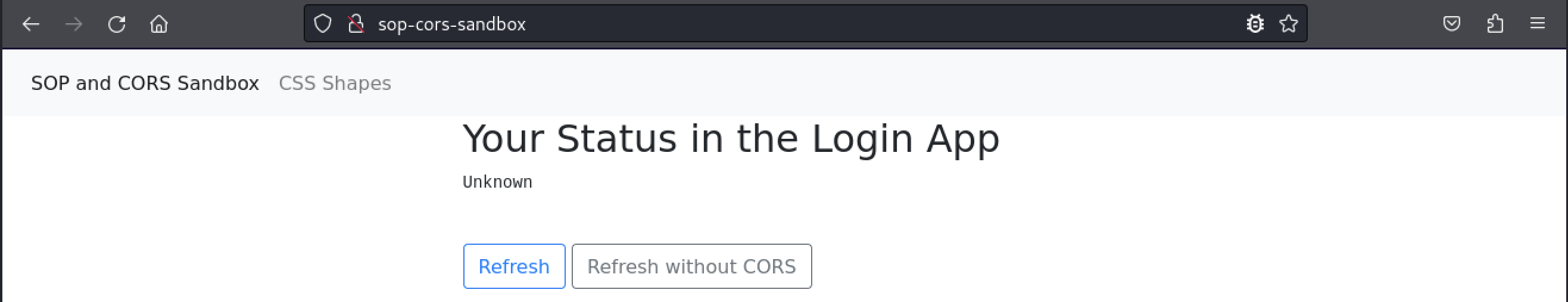

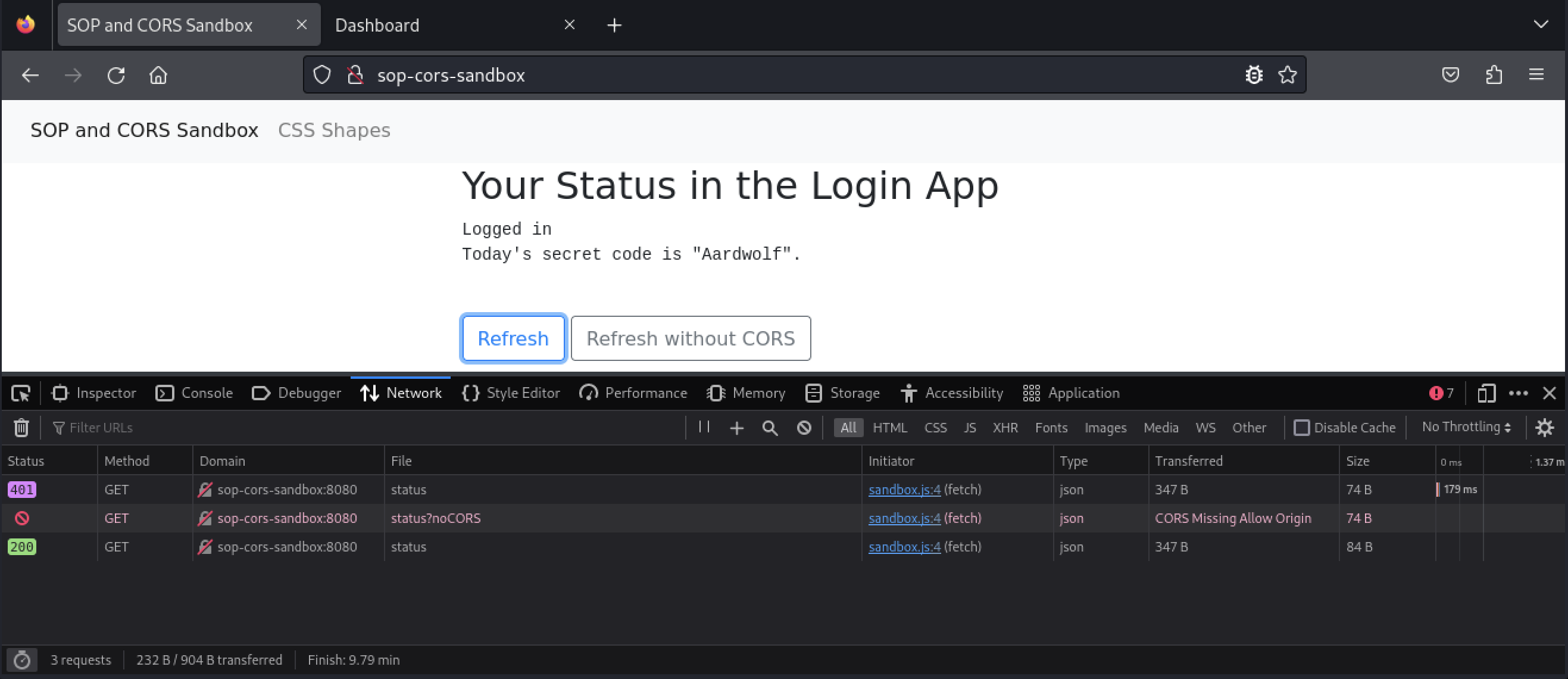

Let’s explore an example of CORS in the SOP and CORS Sandbox VM. The VM has two web applications. One application runs on port 80 and the other runs on port 8080. Let’s start by browsing to the application on port 80 at http://sop-cors-sandbox/.

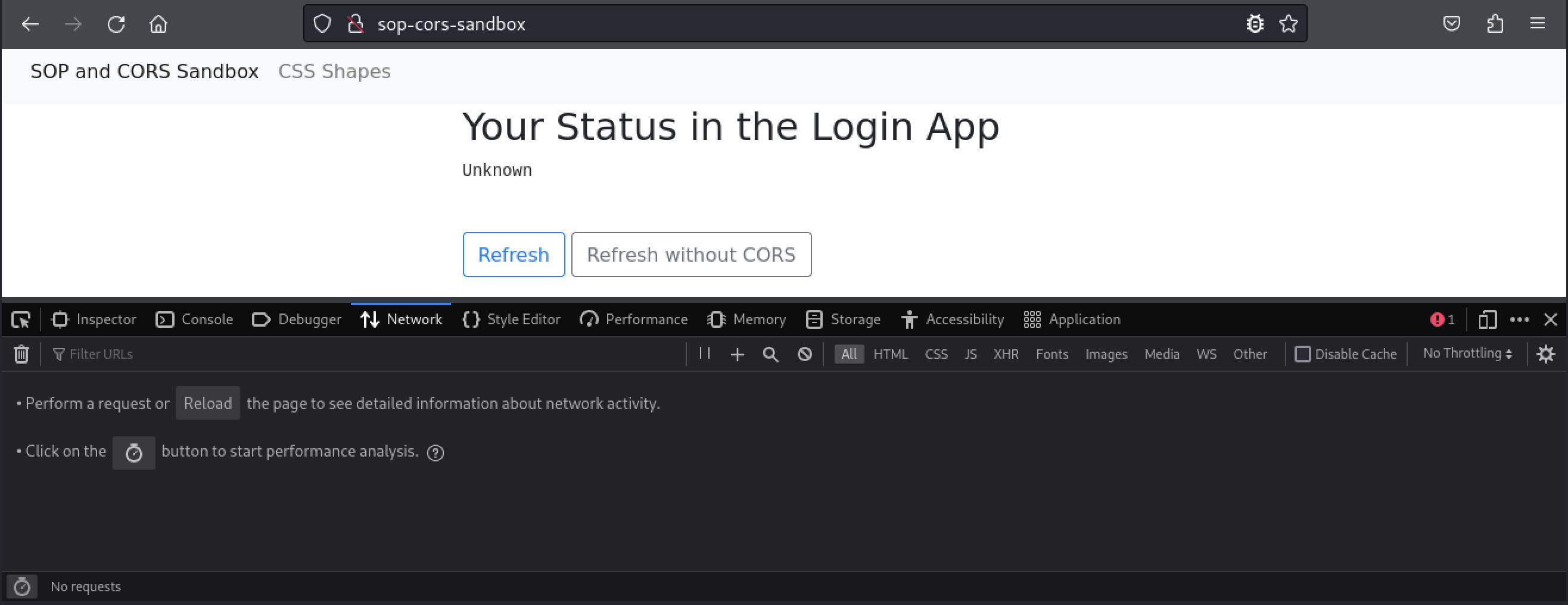

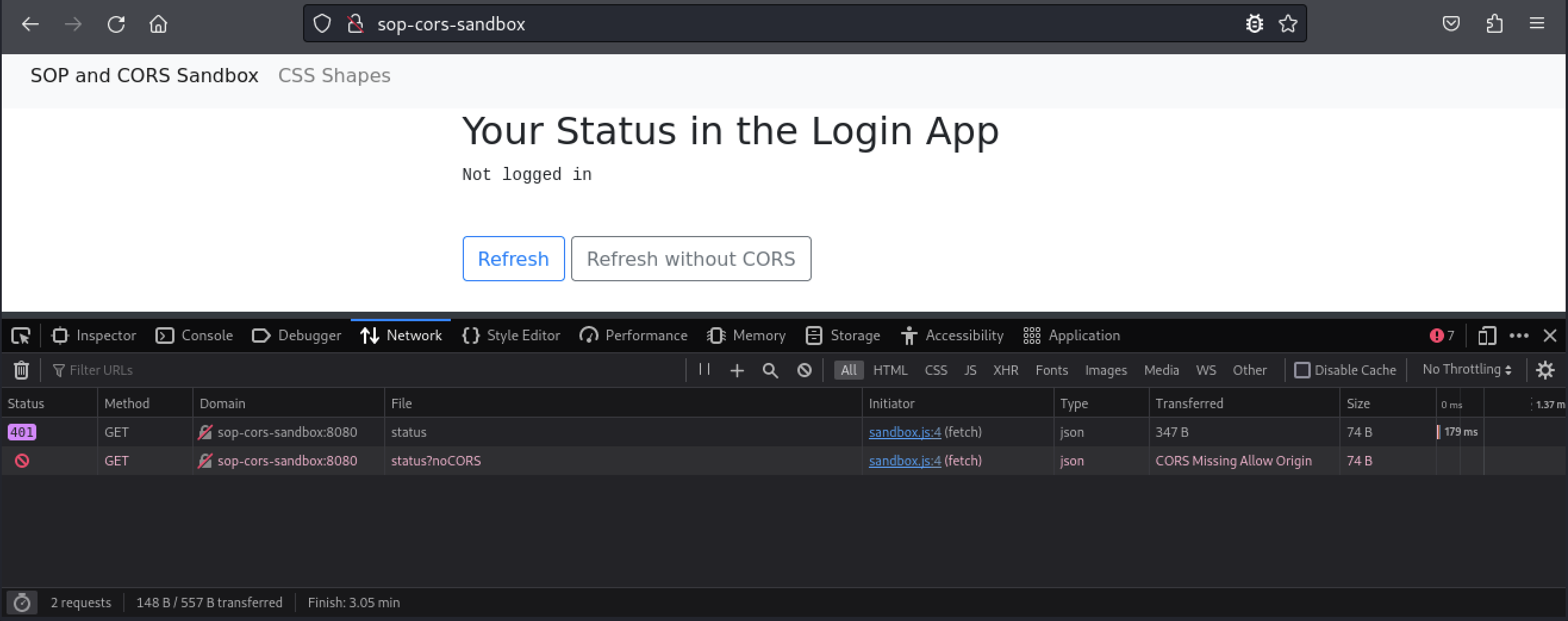

This web page has two buttons. Both buttons will trigger JavaScript code that will check our status in the secondary web application running on port 8080. Our initial status is “unknown”. Before we do anything else, let’s open our browser’s development tools with + and then click Network so that we can inspect the requests sent by this page.

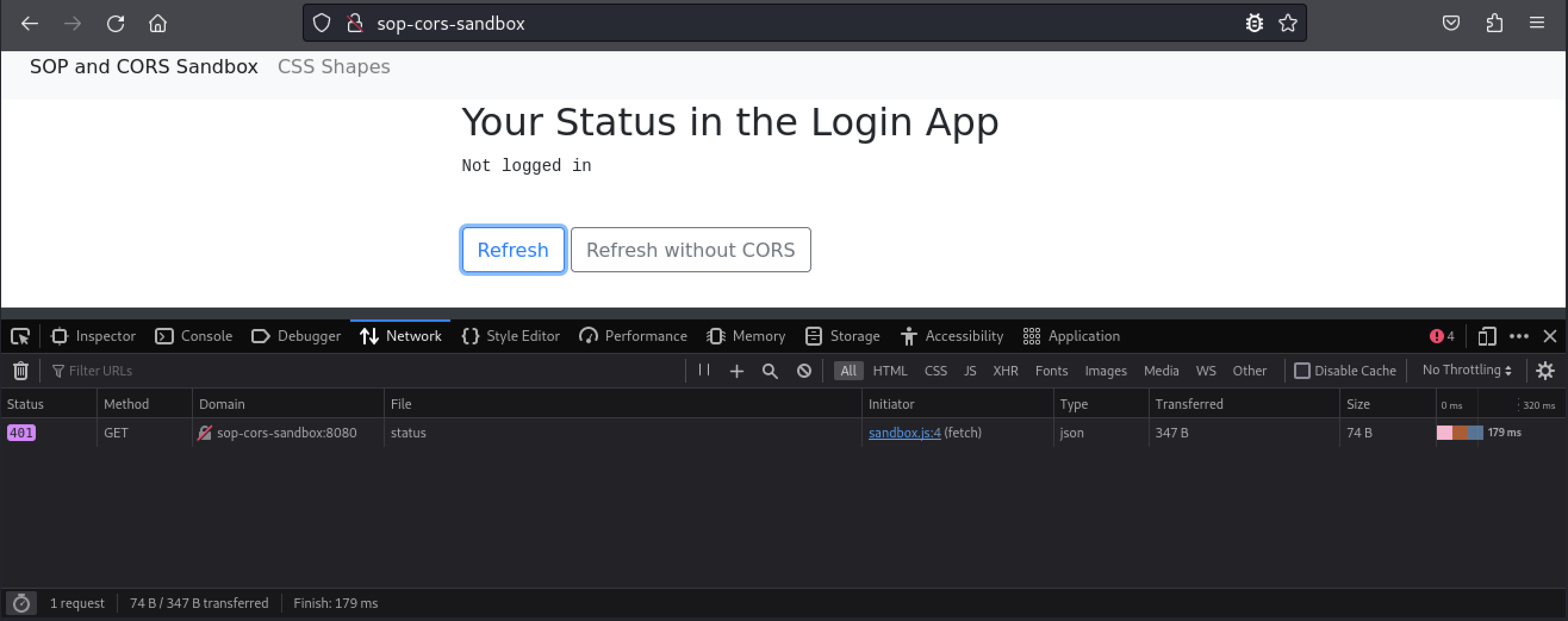

Next, let’s click the Refresh button.

The page sent a request to port 8080 and updated our status to “Not logged in”. For now, we are just exploring the behavioral differences between SOP and CORS. With that in mind, let’s click the Refresh without CORS button.

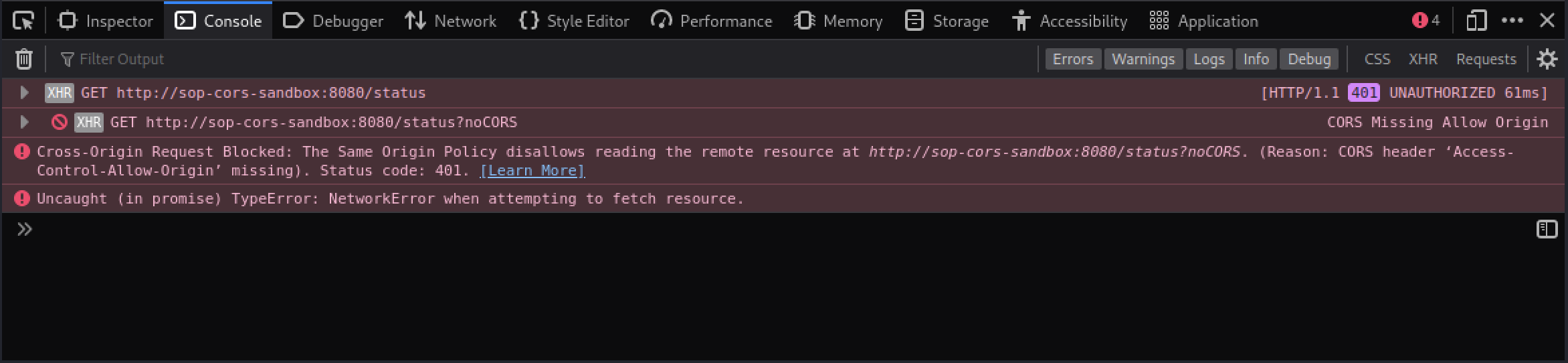

The page didn’t change our status, but the Network tab shows the request’s status as blocked. If we switch to the Console tab, we get a more verbose message.

The third error message states “The Same Origin Policy disallows reading the remote resource…”. Applications must explicitly enable CORS to bypass the same-origin policy. Even though both applications are running on the same domain, the applications have different origins since they are running on different ports.

Let’s clear the console output by clicking on the trash can icon in the upper left corner of the Console tab and then switch back to the Network tool.

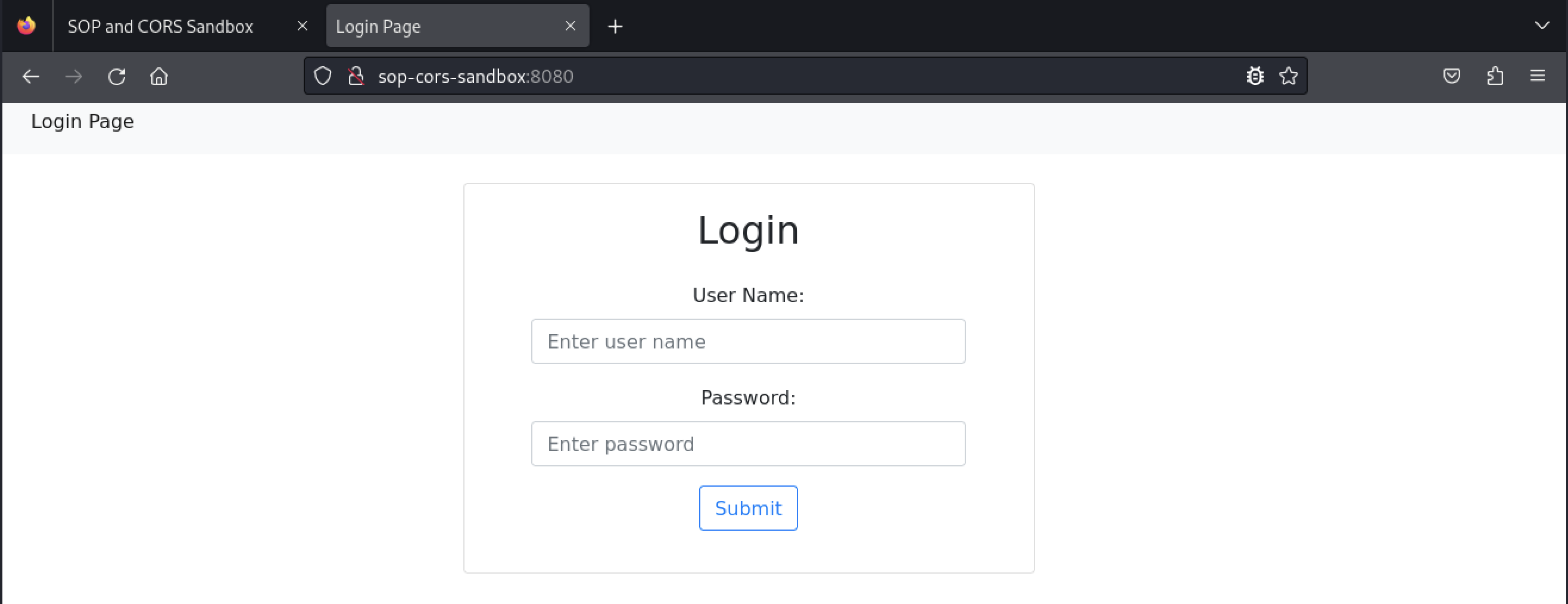

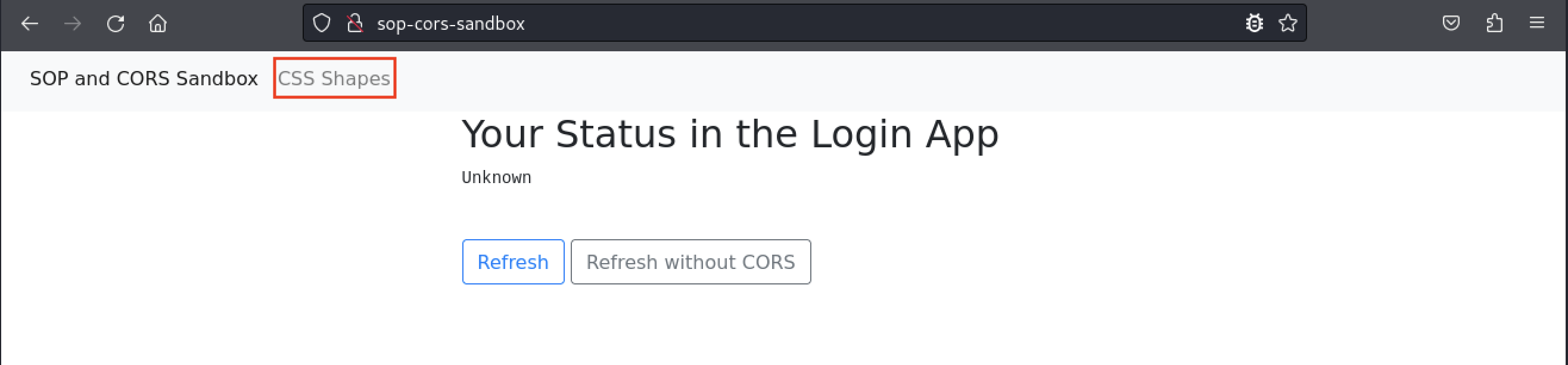

Next, let’s review an example of the page using CORS to access data from a different origin. We’ll open a new tab in our browser and navigate to http://sop-cors-sandbox:8080/.

We can log in with the username “student” and the password “studentlab”.

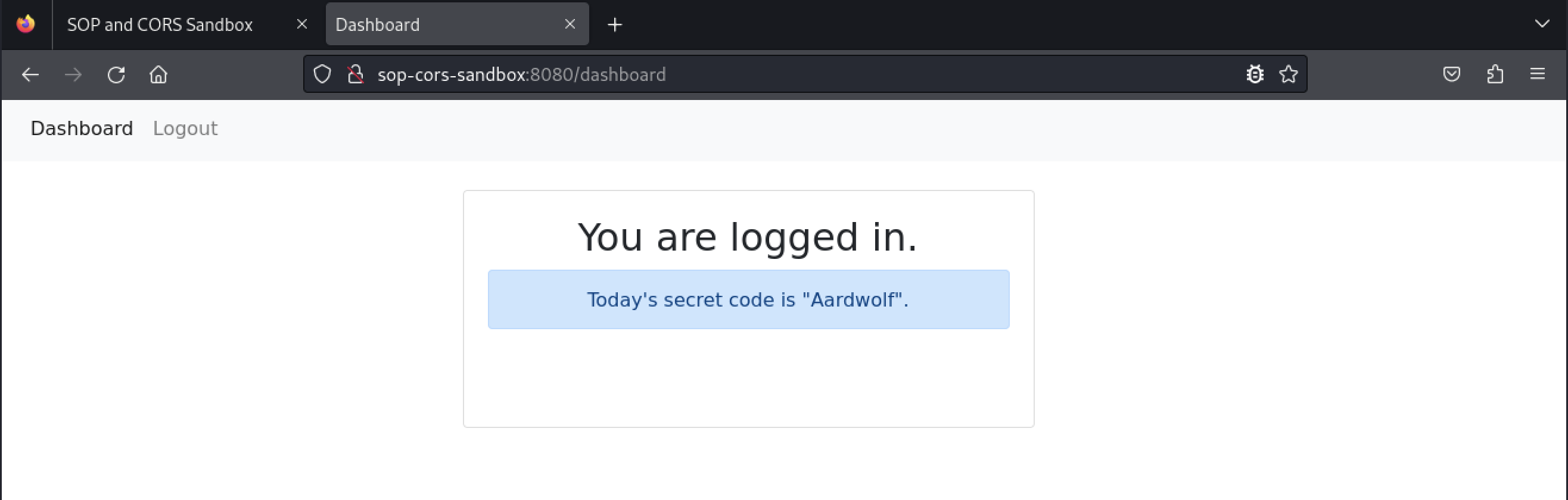

Once we are logged in, we can view today’s secret code. Let’s switch back to the browser tab with the sandbox page and click the Refresh button.

The CORS request returned an HTTP 200 response, and the page displayed the secret code. This basic example illustrates how one origin (the sandbox application on port 80) can access data from a different origin that implements CORS (the application on port 8080). The application on port 80 was able to read the responses of the CORS requests sent to port 8080 and display the contents within the web page. If the web application on port 80 contained any malicious JavaScript code, that code would also be able to read the CORS responses and exfiltrate the data or perform actions on behalf of the user logged in to port 8080.

While both applications in this example are running on the same host, they have different origins. This example would be functionally the same if the two applications were running on different servers.

Next, we’ll review the HTTP methods and headers that CORS uses.

OPTIONS and Preflight Requests

To follow along with this section, start the VM in the Resources section at the bottom of this page.

Before sending most cross-origin requests, the browser makes a preflight request to the intended destination using the OPTIONS HTTP method to determine if the requesting domain may perform the requested action. All cross-origin requests, including the preflight request, usually include an Origin1 header with the value of the domain initiating the request.

Let’s review an example of a preflight request.

1

2

3

4

OPTIONS /example HTTP/1.1

Host: bar.com

Accept: text/html

Origin: foo.com

The preflight request uses the OPTIONS HTTP method and includes an Origin header. This header informs the remote host what origin initiated the request. In this example, the foo.com origin initiated the request to the bar.com site. An OPTIONS request does not include a body.

While our browser will automatically send preflight requests when necessary, we can use other tools to send OPTIONS requests. This is basically what the browser sends. Let’s try sending an OPTIONS request with curl.2

We’ll specify -v to enable verbose mode, which will display request and response headers in the output, set the OPTIONS method with -X, and finally, our URL.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

kali@kali:~$ curl -v -X OPTIONS http://sop-cors-sandbox/example

* Trying 192.168.50.155:80...

* Connected to sop-cors-sandbox (192.168.50.155) port 80 (#0)

> OPTIONS /example HTTP/1.1

> Host: sop-cors-sandbox

> User-Agent: curl/7.79.1

> Accept: */*

>

* Mark bundle as not supporting multiuse

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET,OPTIONS

< Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

< Content-Length: 0

< Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

< Date: Wed, 16 Nov 2022 21:10:32 GMT

< Server: waitress

<

* Connection #0 to host sop-cors-sandbox left intact

Lines that start with “>” in the output are the request. Curl sent an OPTIONS request without an Origin header since we did not specify one.

Lines that start with “<” are the response. The response includes two headers that start with Access-Control,3 which indicates the server supports CORS.

Some cross-origin requests do not trigger a preflight request. These are known as simple requests,4 which include standard GET, HEAD, and POST requests. Simple requests must also use standard content-types, which include application/x-www-form-urlencoded, multipart/form-data, and text/plain, to avoid preflight requests. However, other request methods, requests with custom HTTP headers, or POST requests with nonstandard content-types, such as application/json, will require a preflight request.

A preflight request can include additional CORS-related headers. We will examine the common CORS request headers in the next section.

CORS Request Headers

To follow along with this section, start the VM in the Resources section at the bottom of this page.

Preflight and CORS requests can include additional headers besides the Origin header. Let’s review an example of an OPTIONS request with two additional CORS headers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

OPTIONS /foo HTTP/1.1

Host: megacorpone.com

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-us,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip,deflate

Connection: keep-alive

Origin: https://offensive-security.com

Access-Control-Request-Method: POST

Access-Control-Request-Headers: X-UserId

The Access-Control-Request-Method header indicates which HTTP method the browser intends to send on the subsequent CORS request.

The Access-Control-Request-Headers indicates any headers the browser might include on the subsequent CORS request.

Both headers can include a single value or a comma-separated list of values.

The browser inspects the server’s response to determine if it should send the actual request.

If the request is a simple request (GET, HEAD, and POST with standard content-types), the browser will send it with the appropriate CORS headers without first sending a preflight request.

We can add headers to our requests in curl with the -H option followed by the header and its value in double quotes. Let’s try sending an OPTIONS request to our sandbox VM with an Origin header with the value “foo.bar”. We’ll also set -I so that curl only displays the response headers. By default, setting -I will send a HEAD request, so we’ll need to set -X OPTIONS to send an OPTIONS request.

If we wanted curl to output the response headers and the response body, we would use -i or –include instead of -I.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

kali@kali:~$ curl -I -X OPTIONS -H "Origin: foo.bar" http://sop-cors-sandbox/example

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: OPTIONS

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: foo.bar

Content-Length: 0

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Date: Wed, 16 Nov 2022 21:35:18 GMT

Server: waitress

The application responded back with the Origin value we sent in Access-Control-Allow-Origin. We’ll explore several Access-Control-Allow-Origin headers in the next section.

CORS Server Headers

To follow along with this section, start the VM in the Resources section at the bottom of this page. While the application is like the examples in the previous section, it is configured differently.

Now that we know how to send an OPTIONS request, let’s review an example of how an application might respond. This example includes four common CORS headers an application can set on a response.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET, POST, OPTIONS

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://foo.com

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: X-UserId

Cache-Control: no-cache

Content-Type: application/json

Connection: close

Content-Length: 15

{"status":"ok"}

The Access-Control-Allow-Origin1 header indicates which origins are allowed to access resources from the server. A wildcard value (*) used in this header indicates any origin can access the resource. Generally, servers should only use this setting for resources that are considered publicly accessible. The header can also specify a single origin. If an application needs to allow multiple origins to access it, the application must contain logic to respond with the appropriate domain.

The Access-Control-Allow-Credentials2 header indicates if the browser should include credentials, such as cookies or authorization headers. The only valid value for this header is “true”. Instead of setting a “false” value, servers can simply omit the header.

To set the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials value to “true”, the web application must set a non-wildcard value in the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header.

However, the browser will enforce the SameSite attribute on any cookies that it would send cross-origin, regardless of the destination’s CORS settings. In other words, if the cookie has SameSite=Lax, the browser will not send it even if the preflight request indicates that the destination server allows credentials on CORS requests.

The Access-Control-Allow-Methods3 header indicates which HTTP methods cross-origin requests may use. The header value can contain one or more methods in a comma-separated list. For example, the following value indicates the server allows requests with GET, POST, and OPTIONS methods:

1

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET, POST, OPTIONS

Similarly, Access-Control-Allow-Headers4 indicates which HTTP headers may be used on a cross-origin request. The header value can contain one or more header names in a comma-separated list. Browsers will consider some headers, such as Content-Type, safe and therefore, always use them in cross-origin requests.5

Servers must use the Access-Control-Allow-Headers header to allow the authorization header or custom headers on CORS requests.

There are two other CORS headers that are less common.

Access-Control-Expose-Headers6 indicates which response headers JavaScript can access. This header is very similar in concept to Access-Control-Allow-Headers, but only applies to the response. It has its own list of safe headers that can always be accessed by the calling application.7 These headers, such as Content-Type and Content-Length, don’t have additional meaning within CORS so we won’t review them.

The Access-Control-Max-Age8 header indicates how long the browser should cache the results of a preflight9 request.

We can check response headers in several ways, such as using our browser’s network tool or using curl. Some servers will only respond with CORS headers if the request includes an Origin header.

Exploring CORS Revisited

Now that we have a better understanding of CORS and the headers it uses, let’s review another example. Our previous example in the SOP and CORS Sandbox used JavaScript to send CORS requests. There are other times that browsers will use CORS in certain situations when JavaScript or CSS will interact with an image or font on a different origin.

In the case of fonts, this only applies to the @font-face1 rule loading fonts from other origins.

Images and videos in tags are not subject to CORS. However, CSS shapes2 from images,3 WebGL textures, and drawing images or video to a canvas using drawImage()4 are all subject to CORS when loading resources from other origins.

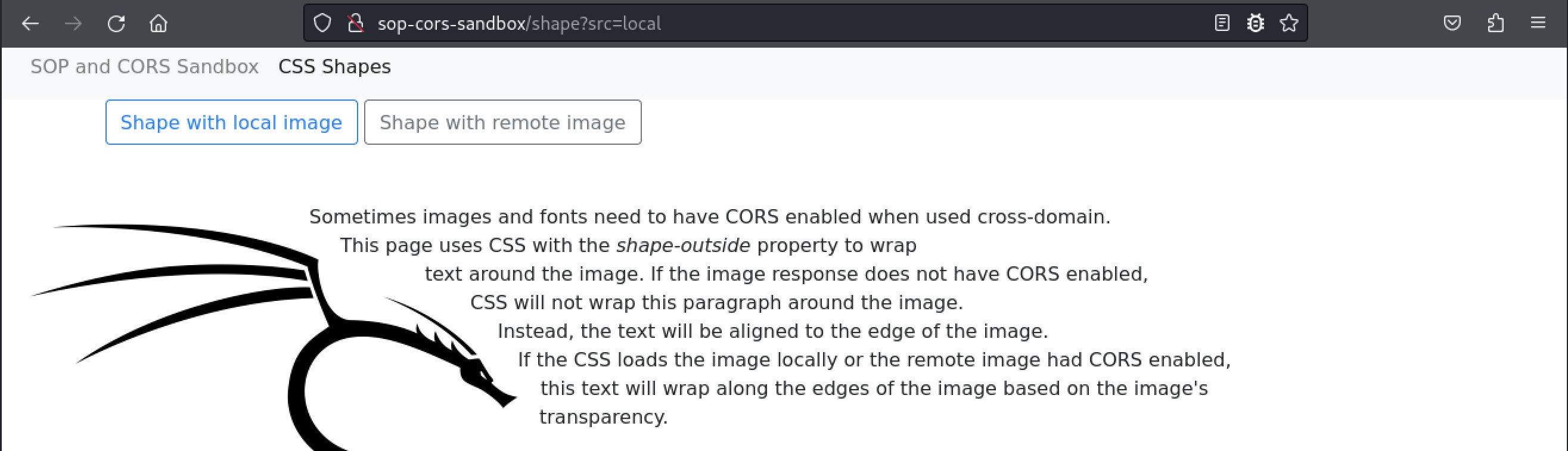

We can find an example of this in the SOP and CORS Sandbox. We’ll browse to the sandbox page at http://sop-cors-sandbox/ and then click CSS Shapes in the navigation bar on the top of the page.

After we click the link, our browser will load a page that uses a CSS shape from an image.

This page uses a CSS shape from an image to wrap the text around the image based on where the image’s transparency is. The page has two buttons that allow us to load the shape information from a local image or a remote image.

Let’s inspect the page’s source to understand how the page defines and uses a CSS shape. We’ll right-click on the page and then click View Page Source. The page defines a CSS class on lines 11 - 18 and then uses the class on an image on line 43.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11 <style>

12 .kali {

13 float: left;

14 shape-outside: url(/assets/images/kali.png);

15 shape-image-threshold: 0.5;

16 shape-margin: 20px;

17 }

18 </style>

...

43 <img src="/assets/images/kali.png" alt="Kali dragon" class="kali">

The kali CSS class sets the shape-outside property with a local URL on line 14. On line 43, the HTML declares an image element with a local URL and the kali class. Since the shape-outside property uses a local URL, CORS does not apply to the request.

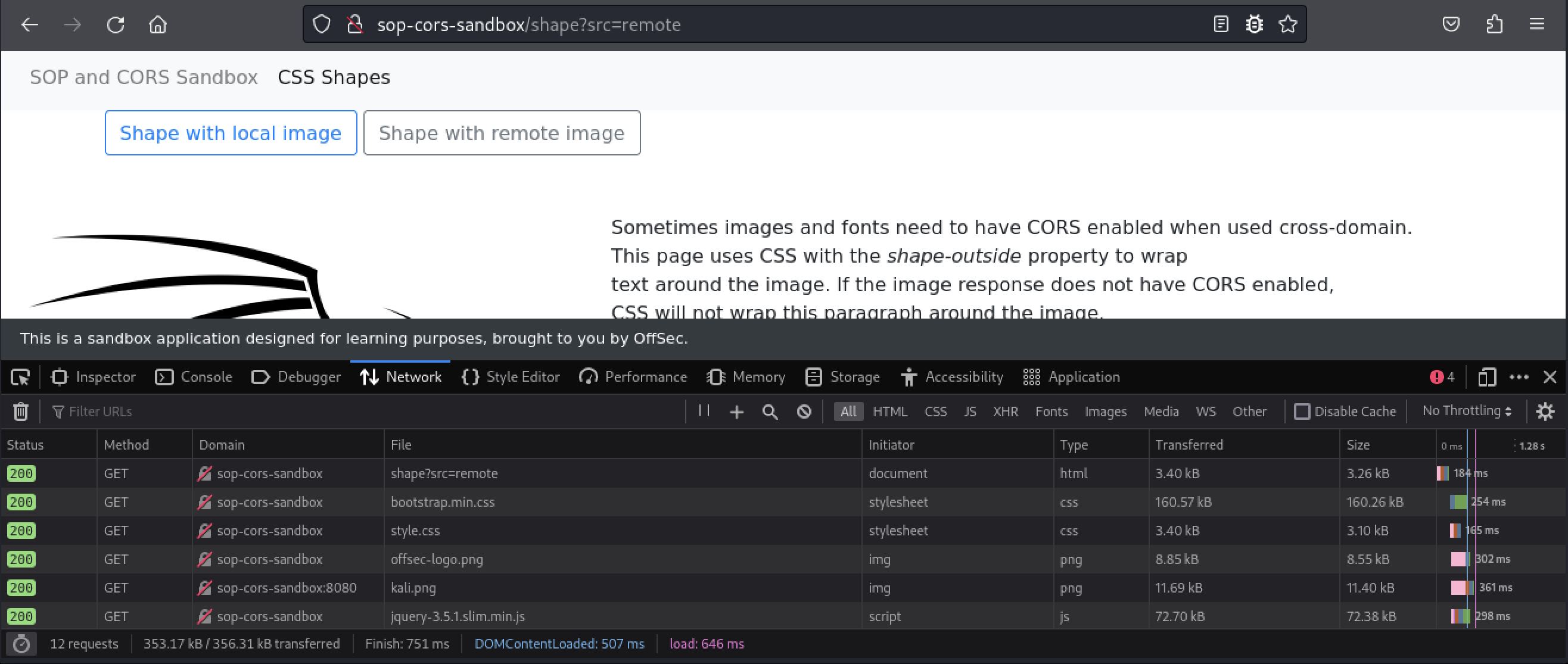

Let’s try the remote image option, but first we’ll open our browser’s development tools with + and then click Network so that we can inspect the requests sent by this page. Next, we’ll click the Shape with remote image button.

The text on the page no longer wraps around the image based on the image’s transparency. Instead, the text content aligns with the image’s right side.

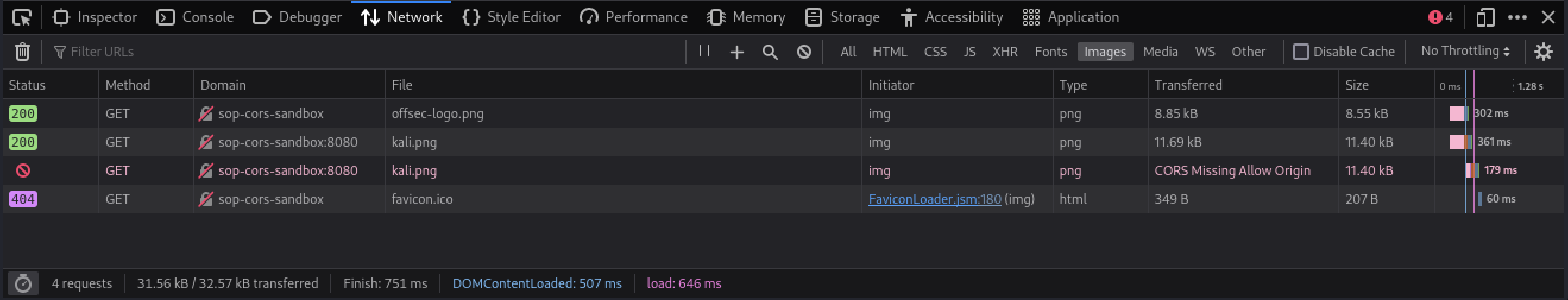

In the Network pane, let’s filter the requests for just images by clicking on Images.

There are two requests for http://sop-cors-sandbox:8080/kali.png. However, only one request returned a valid response. Our browser blocked the other response because it did not include CORS headers.

Let’s inspect the page source again to determine how it aligns to these requests.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11 <style>

12 .kali {

13 float: left;

14 shape-outside: url(http://sop-cors-sandbox:8080/assets/images/kali.png);

15 shape-image-threshold: 0.5;

16 shape-margin: 20px;

17 }

18 </style>

...

43 <img src="http://sop-cors-sandbox:8080/assets/images/kali.png" alt="Kali dragon" class="kali">

The shape-outside property on line 14 uses a cross-origin URL, as does the image element on line 43. Browsers do not enforce CORS when an image element loads an image from another origin. Our browser still loaded the remote image and displayed it in the page. However, browsers will enforce CORS on remote URLs with the shape-outside property since the browser’s CSS engine would modify the page’s DOM based on the image’s content.

This example demonstrates how browsers require CORS on some resources based on how a web page loads them.

CORS Security Concerns

Our sandbox application demonstrated how one application can access data from a different application or origin that has CORS enabled.

By its very nature, CORS weakens or removes the protections of the same-origin policy. Websites that enable CORS can leave themselves and their users open to CSRF-style attacks if there are any weaknesses or misconfigurations in the site’s CORS settings.

When misconfigured, attackers can exploit CORS to perform actions in a user’s session through client-side attacks.

The Access-Control-Allow-Origin header can be particularly problematic. As previously mentioned, this header can be set to a wildcard or a single origin. If we want our application to trust more than one origin, we must implement that logic in our application or framework.

Trusting any origin by reflecting the Origin header from the request effectively disables the SOP for all domains. This can have disastrous implications as any origin could then issue requests on behalf of the user and obtain the full responses.

Sending Requests Between Origins

Moreover, since we already understand CORS and SOP next key concepts are important:

- Understand how to use XMLHttpRequest

- Understand how to use Fetch

Now that we understand SOP and have explored how applications enable CORS, let’s review a few ways to send cross-origin requests with JavaScript.

XMLHttpRequest

Although its name includes XML, the XMLHttpRequest (XHR)1 object can send HTTP requests of any data type.

We can find an example of this function in the SOP and CORS Sandbox at http://sop-cors-sandbox/assets/scripts/sandbox.js starting on line 18.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

18 function checkStatusXHR(withoutCors) {

19 let url = constructURL(withoutCors);

20

21 var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

22

23 xhr.onreadystatechange = function() {

24 if(xhr.readyState == 4) {

25 var res = JSON.parse(xhr.responseText);

26 if(res.status == "ok"){

27 $('#status').text(res.message + "\n" + res.code);

28 } else {

29 $('#status').text("Not logged in");

30 }

31 }

32 }

33 xhr.withCredentials = true

34 xhr.open("GET", url, true);

35 xhr.send();

36 }

Line 21 creates a new instance of the XMLHttpRequest object. Lines 23 through 32 declare a function to handle the readystatechange event. The event triggers whenever the readyState property changes, such as when the object opens a connection, sends data, downloads data, or the operation is complete. Once the operation is complete (readyState == 4), the responseText property will contain the response.

Line 25 parses the response as JSON. Lines 26 through 30 update the page based on the contents of the response. Line 33 sets the withCredentials property to “true”, which instructs the XHR object to send cookies on the request. Line 34 calls the open() method and passes in three parameters. These parameters are the HTTP request method, the URL, and if the request should be handled asynchronously.2

JavaScript code can run synchronously or asynchronously. When running synchronous code, each operation must complete before the next one executes. Asynchronous code allows execution to continue while waiting for some operations to complete.

Since the function sends the request asynchronously, the event handler function on lines 23-32 is required to handle the HTTP response when it is available. In other words, the xhr.onreadystatechange event executes when there is a change in the xhr object. If the code didn’t include a function to handle the event, it couldn’t do anything with the response, such as update the page.

Finally, line 35 calls the send() method. As the name suggests, this method sends the request to the server.

XHR will automatically handle preflight requests if necessary. However, it will only attempt to send cookies cross-origin if the withCredentials property is set to “true”.

Fetch

The Fetch1 API is an interface for sending HTTP requests like XHR, but is easier to work with and more flexible.

We can find an example of this function in the SOP and CORS Sandbox at http://sop-cors-sandbox/assets/scripts/sandbox.js starting on line 1.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

01 function checkStatusFetch(withoutCors) {

02 let url = constructURL(withoutCors);

03

04 fetch(url, {

05 method:'GET',

06 mode:'cors',

07 credentials:'include'

08 }).then(response => response.json())

09 .then((data) => {

10 if(data.status == "ok"){

11 $('#status').text(data.message + "\n" + data.code);

12 } else {

13 $('#status').text("Not logged in");

14 }

15 });

16 }

Lines 4 through 8 call the fetch() method and pass in a URL and an object containing custom settings (lines 5 through 7). Unlike the XHR example, the code declares the request should be sent as CORS (line 6) and that credentials (cookies) should be included (line 7). Developers can use the custom settings object to configure many aspects of the resulting HTTP request, such as the request method, arbitrary headers, request body, and more.

The Fetch API returns a Promise2 object and sends requests asynchronously. A Promise represents a value that will be known after an asynchronous operation completes or errors out. We can think of Promise objects as placeholders. We know some value will be returned, but we don’t know what the value will be until it is returned. In the case of the Fetch API, the Promise becomes a Response3 object once the remote server responds. This code uses then()4 functions and arrow functions5 to handle the Promise and Response objects.

Once the Response object resolves, the first arrow function extracts the response’s JSON body with the json() method (line 8). The code passes the JSON body to the next arrow function, which updates the page’s content based on the JSON values (lines 9-14).